Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

In this cold and wet December, when rain comes suddenly and unapologetically, we crawl the Southern Route to Batangas City, gritting our teeth through slow traffic in areas where road widening seems to extend forever. In my brother’s “garden suite,” where he was forced to cage his dogs for a day, messages poured into our FB thread called Batangas Peeps:

“On the way na.”

“Malapit na.”

“Stuck lang konti sa traffic po.”

“Lakas po ng ulan dito ngayon.”

Meanwhile, my sister dons her event planner/organizer persona, decorating our venue. My sister-in-law assists her (though the place is hers), supplying all demanded party plus-plus: tables, a Christmassy background for picture taking, Santa Claus socks hung on a flimsy but cute décor. She even bought new chair pillows.

Honestly, this is already enough reason why I can’t treat our family reunion as optional.

As the house slowly filled and nephews and nieces, with their little ones, came eagerly in cars loaded with gifts, laughter rose even before greetings were completed. Someone immediately asked if the food was enough, but no one needed to worry. Family brought pancit, lumpiang shanghai, sinaing na tulingan, embotido, humba, nilagang sitaw at kalabasa, Jollibee fried chicken, suman sa lihiya, suman sa gata, puto, kutsinta, chocolate tart, piña, grapes, saging—too much food in fact, that after the party, everybody brought home a Sharon share of the pot.

We ate with enthusiasm and without restraint, because this is a no-holds-barred affair: you eat without apology, knowing that tomorrow you will still be family. For me, the excess food was symbolic of God’s ample grace. There is always enough. The reunion reminds me that abundance is the rule of God’s blessings; scarcity is never the norm in His economy.

We did our traditional gift giving, everyone gives everyone a gift. As usual, we don’t really care what the actual gifts are. They are often perky, cute, sometimes corny, sometimes weird. But it’s not the price; it’s the thought. That someone thought of you, picked something with you in mind, wrapped it with care, wrote your name on the tag, and handed it over with a smile.

As I shopped, wrapped, and handed my gifts to every member of the family, I was conscious of how much I’ve always prayed for each one by name. Remembering them this Christmas is only a segment of that routine.

Then came the games with my nephew as emcee, now a pro at inventing games that make everyone temporarily lose their dignity. Simple, easy mechanics that everyone ignores anyway. Laughter explodes when someone is eliminated. Raffle prizes, small and actually, what are they? are announced with exaggerated suspense. Someone complains her name was never put in the jar. Losses are disputed loudly. Wins are celebrated like championships.

In this ritual, silence would have felt wrong.

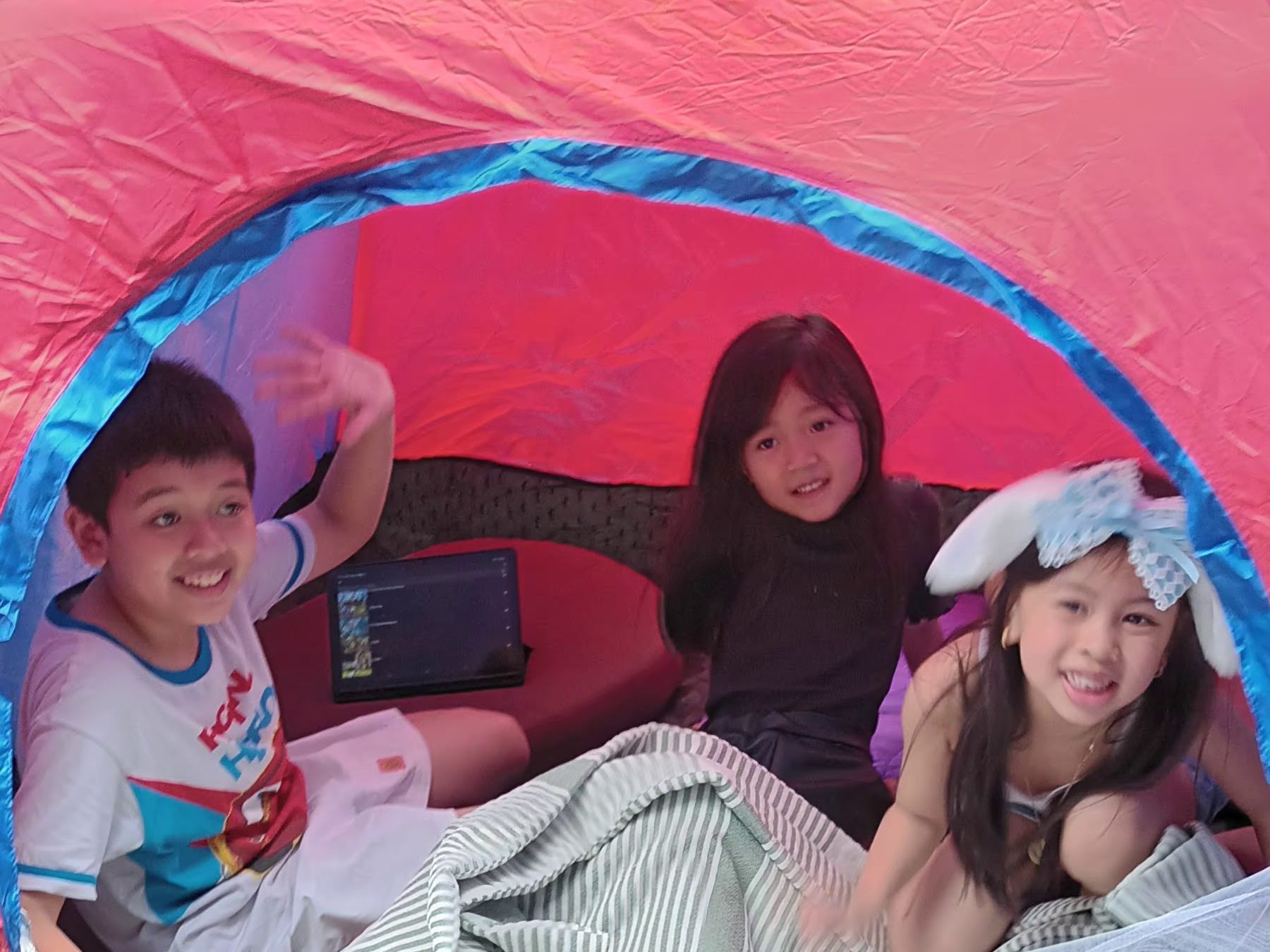

The kids set up camp. My brother placed a tent in one corner of our meeting place, so it became their headquarters. Inside, they secretly ate candies their parents warned them about, opened their tablets, and played Minecraft, zipping the tent closed so no adult could say, “Stop the tablet!”

Their shrieks and laughter sometimes rose above adult chatter. And I’m reminded: reunions are also about letting the children feel what it means to belong to a family. It’s not the rain or the traffic they’ll remember. It’s the tent. The cousins. The feeling of being known.

Meanwhile, us adults wanted updates. We annoyed the Gen Z nephews and nieces with questions about work, plans, dreams, love lives. We masked our curiosity with tender urging, wanting to know where they stand on the edge of becoming.

One nephew, fresh from a government office where the budget miraculously returned, got roasted for being part of the “suddenly-rich” squad, “financially enabled,” as we teased, while he grinned and pretended not to flex his new status. Meanwhile, our January bride-to-be basked in the spotlight as we cornered her fiancé, dragging him into the games and threatening (with dramatic flair) to boycott the wedding if he dared to sulk or sit out. Everyone else got the mock-warning too: cross our niece and consider yourself “disinvited”, family banter code for we adore her and you better, too.

A full house does something to my spirit. It reminds me I am part of something that did not begin with me and will not end with me.

This gathering is not merely convenient. It is necessary.

Everything can be postponed, rescheduled, or attended virtually. But a family reunion resists isolation. It insists that showing up matters, that presence is irreplaceable.

Bodies in one space, voices overlapping, shared meals, curious interrogations, these are not optional extras squeezed into a busy life. They are the scaffolding that holds our personal histories together. Before we became busy, accomplished, tired, or carefree, this is where we were: this family. We see one another not as roles, but as people, growing, aging, changing, maturing.

My brother made sure the sound system was loud enough to disturb the barangay. There was dancing, picture-taking, and eating with our hands or disposables, with a trash can just nearby to avoid an eventual mess. Families wore coordinated outfits, that is, one color per unit. My sister-in-law made sure everyone went home with ham and a bag of leftovers.

The family reunion is a gift. It’s something nobody should miss, even just for the assurance of a presence that enlarges the heart and lifts the spirit. When the afternoon was dim enough for everyone to go back to their busy lives, we stretched our goodbyes, returning tables and chairs to their corners. In this Christmas gathering, where everybody made sure they were present, we had some happy rest in our family’s embrace.

Sometimes, I write not out of inspiration but unrest. In my quiet hours at ninangj@wordhouse, I find myself asking, “How do I turn my small, uneasy moments into meaning? How does writing itself become a prayer?”

Most days, I write not because something dramatic has happened, but because something indulgent won’t leave me alone. Worrying about finances. How to respond in love in a difficult relationship. Wishing for a house with a view. Are these my stories? If I am going to be “authentic,” these are the major concerns humming endlessly in my ears. I pray through all these voices of unrest.

Most days, I am simply going through the motions. Sometimes, I drag myself. Sometimes, I have to will the energy and force the writing, like this one. Most mornings this week, I did a prayer walk at the amenity garden of the condo, and today, I walked again from where I had breakfast up to this co-work space I occasionally use when I’m in the BGC area.

An eleven-minute walk, this is what the directional map Google search told me. Imagine me walking on 9th Street in my step-in, my laptop bag on my right shoulder, a shoulder bag on the left. Together, they’re quite heavy, my everyday load. This day’s start-up. The plan is simple: I wanted to go to BGC because this is a nice place to walk. Ambling along Bonifacio High Street, I stopped a bit, noticing for the first time a tree with white flowers. I wonder what it’s called. I wish the trees here were labelled. I also wanted to follow through with what the EENT said regarding my vertigo, that I should move more.

But really, I have a problem getting busy these days. There’s just not enough to do. Even my classes have not been that demanding. With only six units this semester, checking papers has become even more demotivating. I finish the tasks too soon, then the hours simply stretch. Not having a scholar’s mindset or constitution, I’ve not focused on research as professors should. The books I’ve bought remain piled up, unread. I took a picture of the spines from the corner of my desk to remind myself that I should, I must read. There’s plenty of time to read now, but I lack the desire I had before when reading was still a joy. I hope I’m not falling into a mild depression here, but it seems this is what’s happening.

There are the occasional translation projects, medical reports and trade agreements sent by international clients. Occasional, however, is the curse here. The job orders come unpredictably, whereas before, I used to receive them every day. I was a machine then, translating almost nonstop. But now, AI seems to have taken more and more of what used to come to human hands.

I can’t even argue with it. The machine is faster, tireless, and can process far more than my usual 1,500-word limit per day as a full-time professor doing this part-time. (This is for manual translation or proofreading or editing. With linguistic validation, half is the word limit.) It doesn’t pause for a walk, for coffee, or for that occasional texting to friends or relatives, those small gestures that remind me I’m not that isolated. Still, I had been hoping I could get by again with these rushed jobs that once paid my bills on time.

I’m in the red these days. Each workday feels unsteady and worrisome, as if the floor I’m standing on keeps shifting, like this vertigo I’m taking meds for, and the meds are so expensive. When I check my email, it’s with a small prayer that something will appear: a client, a project, an opportunity for writing. Even co-writing would be welcome. Anything. But so far, nothing.

So I tell myself to press on with my personal writing projects instead, but a new problem begins. What do I write about?

Writing, even not as work but as a lifelong interest, a passion, has been waning in my system. I can feel that it doesn’t fill my heart the way it used to. So I’m fighting the lack of inertia, I’m trying to prop myself up with some kind of ego boost or strength, anything to rekindle the spark.

But all I end up with is envy of those who have managed to make it even with just one book published. What do I have to show for all my wanting-to-write apologetics? For all my chanting and rhetoric about writing as “process,” or “discipline,” or “calling”?

I believe I’ve written so much, but mostly about whining like this, scattered across files and drafts and half-formed essays. Book reviews that are really deep appreciations of my times of happy reading. Beginnings and brainstormed chapters for dreamt-of stories, plays, even young adult fiction. (This blog was supposed to be my young adult fiction space, a way to follow through that project about a fictional young girl’s diary. That’s why this blog is called The YA Bow.) Mostly Tagalog poems, still in draft form, waiting for revisions.

There were some published essays, mostly in the ’90s, and nothing much followed. And now, there’s this persistence, or stubbornness, to keep a blog alive in this hardly noticed digital space. I post anyway, despite the nagging feeling that maybe I’m only adding to the noise. Although, how can that be, when I’m hardly read? The site traffic is forgettable, a faint trickle of visits that barely register.

I check the analytics and assess my act. Is this also an expression of faith? To keep writing even when the audience is almost invisible?

There’s an upcoming writing contest, and I’ve been thinking, should I join? If I spend more time thinking about joining and not actually writing, what does that say about me? But this has been a pattern: thinking about the doing rather than doing the thing itself. I scrolled through the contest announcement again and thought, ok, let’s see….

Yet, I can’t find an experience for the theme: peace in war. It’s a heavy theme that I feel demands some kind of suffering that should turn out into revelation. What do I know of peace or of war? There is, of course, an ongoing war against corruption in this country. We have a war against the eroding institutions and consistent bad leadership in this archipelago. How to write about those within a framework of making peace?

Since me, I’m angry right now. I’m angry with how things keep breaking yet the Filipino is supposed to be resilient, patient, tolerant. Does this mean we’re a people with pacifist inclination? How does one not remain angry? In our situation outrage seems the most natural, even the most honest, response. Writing about peace, would that be writing about an ideal, romantic notion of the good and the beautiful? How do I write peace? How do I make space for calm without silencing this anger that feels truer? This could be the real challenge of writing.

I’ve always been inclined toward fiction. I even began drafting a story once about a Sunday school teacher I met long ago, a brave woman who, out of faith and naïveté, walked into what was then called Smokey Mountain. She went there to teach Bible lessons to children, but she soon found herself teaching less and pleading more: for rice, for medicine, for some mercy from the city. Her Sunday lessons turned into social work, sourcing funds to feed the squatters, walking through municipal halls to help families get their birth certificates processed. Many of the locals weren’t even registered at birth, their existence unrecorded, as if poverty itself had erased them from the nation’s books.

I regret not recording her name in my memory. Back then, I was only following up on the funds Christian aid was sending them, too blind to see the real “war” she was fighting every day in that forsaken place. She was waging it quietly, against hunger, neglect, and the apathy of those who had the power to help. I’ve been thinking how I could turn that story into fiction, something forceful enough to carry my anger, because the conditions haven’t changed. Even with Smokey Mountain now flattened and erased, people are still drowning in floods, in landslides, in the corruption that lets both happen again and again.

How do I write peace here? How do I let hope breathe in the same paragraph as despair?

Perhaps I could lean on style, knowing enough from contemporary writers how to manipulate language to embody this kind of material. But how do I write so the words breathe honestly? I’ve started, and the story still isn’t going anywhere. It’s hard when I keep bleeding into the language. The contest deadline looms. Nothing is happening yet, and I’m growing impatient.

I grew up in Batangas, in three homes. The first one, until I was six, was a rented silong on D. Silang Street. Before sunrise, I would run across the street to Ka Ede’s sari-sari store to buy our coffee. Isang gatang lang po, I’d say, as he ground the beans by hand with a wooden, hand-cranked grinder. He poured them into a balinsuso paper wrap, folded neat like a funnel, which I carried home carefully. Soon after, the kapeng barako would be boiling in the takure, and the house filled with its rich aroma as we got ready for the day.

Breakfast was simple. We dipped pandesal in coffee or poured coffee on rice, depending on what was there. We always had fish, sinaing na tulingan or pritong aligasin. I never thought about whether our meals were balanced or not. Inay always put food on the table, and we were never hungry. Only later, when I was already working in Manila, did I realize that those were difficult years for her.

In Batangas, coffee is simply kape. You ask for it plainly: Pagbili nga po ng kape. Outside the province, though, Barako is what people recognize. It has even become a brand. But barako isn’t always a flattering word. Nabarako means outwitted by someone more cunning. Nakakabarako ka ah is said with offense and a hint of warning. Barakuhin is someone likely to get into fights. A barako can even mean a carabao with horns. Matatapang daw ang Batangueno—mga barako.

More from WordHouse: A House for Words, Reflection and Memory

Now, onto the paper fold that holds the coffee. The balinsuso is a funnel-shaped fold, completely closed at the bottom. Ka Edes poured the ground coffee into this triangle and locked the top with a crinkle. I carried it home like dirty ice cream. In those days, they didn’t place anything you bought in plastic supot or labo, so I had to be careful on my way, lest I trip and spill the coffee. I’m not sure if there’s any other secure fold that doesn’t require origami skills, but this one is a classic coffee bag.

Batangas lies along Batangas Bay and is known for its many beaches. Just off its coast is Isla Verde, where the Verde Island Passage forms a strait that connects the Pacific Ocean and the South China Sea. Naturally, fish abound in the market and most Batanguenos can name them. But even up to my college years, I used aligasin to name almost all the long, slim, red-orange fish I ate. Dalagang bukid was rounder, still orange. Hiwas was flat, like a small pagi or stingray. And what Batangueno doesn’t know Tulingan?

My grandmother, Nanay, as I called her, was a fish vendor. I didn’t see her selling in the market, but whenever we were at her house in the ‘bukid‘ as we referred to it, I sometimes woke early enough to join her at the shore. She chose from banyeras of fresh catch, bargaining with fishermen. Later she would sell the fish at tumpok prices in the market. By the time she returned home, a banyera balanced on her head, it was filled with bread, paborita, suman, melon, grated coconut, pakaskas, rice, bihon, and even bars of Safeguard and Ajax detergent. She still wore her apron, still smelled faintly of the market, and always had her wide smile, her eternally red mouth busy with nganga.

Nanay loved to cook for us when we visited. She always served two breakfasts. The first, at sunrise, was utaw or rice coffee with paborita biscuits crushed into it, something that has remained a family favorite. The second was closer to brunch: fried rice with sinaing na tulingan or pinais, and a real sweetened cup of kapeng barako poured over rice.

Our histories are as islanders

My most textured memories always go back to those times of our visits to my grandparents. I can imagine Inay struggling to haul the four of us, since we first had to take a tricycle from our rented place in Dolor Subdivision (this was where we lived when I was eleven; I was the eldest). Then we would cross a hanging bridge in Wawa, Batangas. We four siblings always scared her as we gleefully walked across the bridge, feigning dizziness and delighting in the swing whenever we ran. Afterward, we’d pass through a forest of palms, our slippers tucked like gloves into our hands, as we walked barefoot, laughing at the occasional shallow sinks in the slimy, dark, watery ground. Once we reached solid sand, we would shout the name of our sundo on the other side of the river. Then Mamay or my uncle would come and fetch us in a rowboat.

I’ve long tried to write a story set in that memory. I realize now that I, too, carry an island narrative. My grandparents’ house is gone, taken by storms, quarrying, and the sea. Yet every time I see barako or sinaing na tulingan sold in sealed containers at malls, I am pulled back to Nanay’s kitchen, to her folded nganga leaves, to the balinsuso-style packets she made.

These fragments may never form a complete story, and maybe they don’t have to. Writing them down keeps the memory alive. And who knows, someone else might find in them a piece of their own story too.

Fragments can grow into stories as we keep them on the page.

In my journey as a poet, Tagalog has become the language where my deepest thoughts and emotions find a true home. Fearless Filipino women poets like Benilda Santos, Joi Barrios, Luna Sicat, Beverly Siy, and Genevieve Asenjo are my favorite weavers of language into poems of resilience, spirituality, and the weight and beauty of lived experiences.

Tagalog is where my poems find their truest home, shaped by fierce rhythms and sharp insights. These voices inspire me to listen deeply and shape words that capture intimate moments, quiet struggles, and the pulse of everyday stories in the city. I reach for fragments of their strength, faith, and intimate storytelling, hoping that my poetry will carry the same enduring fire.

Some of my poems reach for language as sparingly as possible. I struggle to choose each word carefully, placing it where it can bear its own quiet weight. I learned some of this from the poetry of Benilda Santos. Her Pali-palitong Posporo showed me how deliberate Tagalog can be, how crisp, short words can open up an expanse of meaning. Lingering on her minimalist expression reveals more than what she’s actually written about grief, faith, and womanhood.

I try to weave in the same way and capture moments by the tones they leave behind. Do I hear the children at the wet market, their quick and thin pleas? The commuters in line, their words swallowed by the brewing storm. Even the mall wanderer’s talk dissolving into the hum in shiny ailes. And that still, silent girl on the LRT to PGH who is burdened with what she could not say.

I’ve never been political. More a coward. Quick to escape rather than confront. But Joi Barrios’s poetry can protest and sing. Resist and still show tenderness. She confronts with melodious verse and deeply felt detail. A woman’s circumstance, often her own, moving through complex political landscapes. I have mimicked this at times. Writing of tired faces on buses and trains. People weighted by the end of the day. Still carrying resilience and hope alongside their sorrow.

When does a poet truly become political? How do poems reveal human rights in the raw edges of everyday life. My subjects are these moments. Commuters braving traffic. Floods. The weight of capitalism on the streets of the Philippines.

I have been writing poems about my faith and the doubts that shadow it. In my book, I have gathered these struggles into three threads: pagtataya, how faithful am I? pagkagulantang, how sensitive? pagpasan, how responsible? Rebecca Añonuevo’s poetry, along with her thesis on Gana, charts many poet’s deep and often complicated dialogue with the Divine. My own poems attempt something similar, mapping the restless terrain of my faith in moments of searching, in whispered encounters with God.

Luna Sicat’s poems delve into desire, memory, and history. Her language enacts distance and isolation. In my own work, I try to capture moments like these: a mother leaving her child to work abroad, a daughter caring for an aging parent, a death in the neighborhood that whispers of systemic violence. I watch the quiet faces passing by, their histories folded in silence, their desires hidden in camouflage. Luna’s poems become voices of silent longings, histories murmured between heartbeats, and dreams that remain unspoken.

Beverly Siy is fearless in speaking her raw, personal truth. Her voice prods one to be brave and speak even when the words are sharp or messy.

I am Batangueña, and sometimes I feel self-conscious about letting my punto slip into my poetry. Batangas Tagalog, as a dialect, can seem inaccessible to some readers, yet I cannot set it aside. It is my language that insists on being spoken.

There is one poet who weaves her native Hiligaynon with Tagalog seamlessly. Genevieve Asenjo writes in three languages and sometimes weaves them all together. This shows me that poems, too, don’t just map a body, but also an archipelago, all the provinces and cities inside me, all the places of home and belonging.

My poems flow in Tagalog, shaped by the stories I hear behind weary faces on buses and trains, in markets and malls, on streets and highways. My essays, however, feel more at home in English. I often struggle to write them in Tagalog, and when I translate for convenience, the result feels like stiff, borrowed clothes. Perhaps it is because of my schooling. In all my education, English essays were graded and assessed, while Tagalog was reserved for spoken stories, warmth, and shared laughter.

My use of Tagalog in poetry comes from a belief in its spirit and depth. Tagalog holds music, rhythm that breathes, and syllables that sway. I court its words to carry both tenderness and bite. English, for me, offers structure and sometimes direct argument. Both languages are mine to use, and I will not compromise context or meaning in either.